Home > On-Demand Archives > Talks >

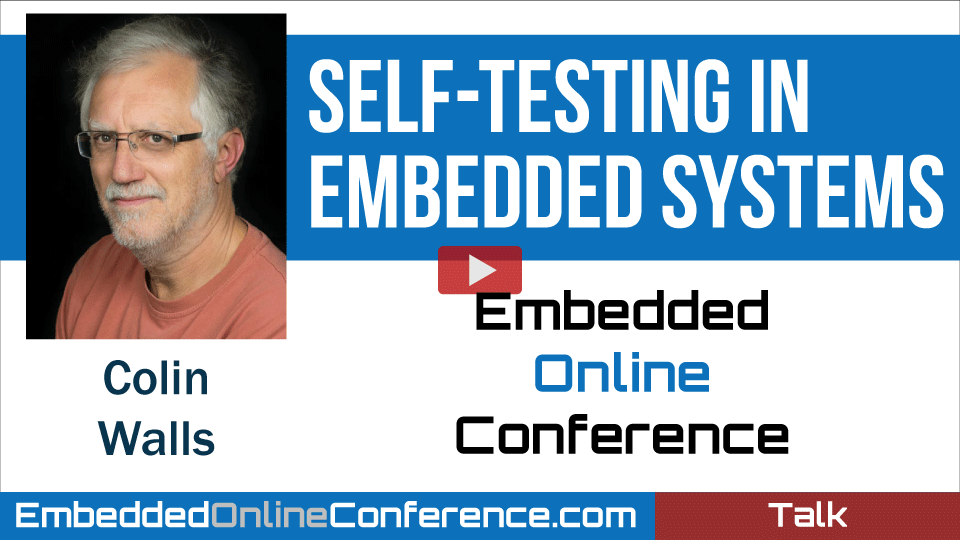

Self-testing in Embedded Systems

Colin Walls - Watch Now - EOC 2021 - Duration: 37:42

Thanks.

An interesting idea. The topic does have potential for more exploration.

Hi Colin, brilliant presentation. In the unfortunate event of having the guarding words on a stack overwritten due to under/overflow, presumably a reset would be the only sensible way out at that point as the task relying on that task would be operating with an undefined context?

This depends on the application. Once the guard word has been corrupted, we know the stack has overflowed, but there is still a chance that nothing else has been corrupted. Depending what the system is, there might be the possibility of going into a "safe state" instead of a full reset, if continuing operation would be highly desirable.

Hi Colin. great talk

I have a question related to self-testing in a coupled system comprised of 2 separate interfaces (PCBs, MCUs, SBCs). Both are equally vital for the overall system to function.

What kind of mechanism would you setup on each side to ensure the overall safe operation of the system?

for example, would you consider using a heart-beat signal on a GPIO that, if not received, will trigger a power reset of the other interface?

would it make sense for the 2 interfaces to share their current state to the other, so that if a reset is needed, they can quickly fetch the latest state?

Thanks.

I would say that, if you have 2 equally vital processors, each one monitoring the other would be a very good approach. You could use either kind of watchdog mechanism. Either a heartbeat that, if it stops, triggers a reset, or a ping that needs a response in a specific timeframe. Which one depends on your software architecture.

Great talk!! I really enjoyed your presentstion. Thank you

Thanks for the feedback.

When testing memory, it's a good idea to put an access to another memory location before reading back the value in the location under test. I've worked with systems that had enough capacitance on the data bus that you would read back whatever you wrote last, which means that write/read/check memory tests would pass even if there was no memory present at that address.

Also, during a pattern test at powerup, adding reads at powers of two can be used to determine memory size, and sometimes whether there's a problem with the address lines.

I assume this is complicated even further by higher end micros now having data caching too...

Definitely!

Thanks Steve. Useful refinements.

I'm not sure I understand how you would use a guard word for protecting against array bounds violations. The stack example seemed easy enough. However, I don't think spinning up a task for every array to monitor the guard word is practical.

You would not have a task for each array. A single task could take on a number of self-testing activities.

Colin, in this talk you say "Don't think a pointer is an address. There's more to it than that." I think I have a pretty good understanding of pointers but I'm wondering if you could briefly elaborate on this statement.

Thanks for a great talk!

Thanks Gary.

The main difference between a pointer and an address is illustrated when you do arithmetic on a pointer. You can increment a pointer in various ways:

int *p;

p++;

p += 1;

p = p + 1;

These are all entirely equivalent. In each case, p is incremented to pint to the next object of type int. As an int is typically 4 bytes, 4 is added to the value of p.

Hopefully this clarifies what I was going on about.

Definitely. I do understand this. I just wasn't quite sure what you meant in the discussion. Thanks for (both of) your reply(s).

Great talk Colin, would you recommend a book to go even deeper on this topic?